As growth slows and currencies depreciate, African countries which have borrowed in foreign currencies risk falling into the same debt traps they barely escap

ed. Bono, are you paying attention?

The turn of the millennium saw the

Jubilee campaign, a massive effort to write off third-world debt. Bono was a leader of an admirable initiative to relieve highly indebted countries of financial burdens which were crippling their abilities to reduce poverty and grow. Much of the debt had been built up illegitimately in countries with weak institutions where the risk of borrowing was not understood; dictators such as Mabuto Sese Seko (Congo) and Idi Amin (Uganda) also amassed large debts which impoverished their respective countries.

The Jubilee campaign

was largely successful, as it saw G7 countries pledge to cancel $50bn worth of debt. The true cost of the write-down is far less, given how little of the debt was actually being serviced. The Jubilee debt campaign has also worked against “vulture funds”, which buy the debt of defaulted countries and then attempt to bring judgements through legal systems in the developed world. Zambia faced an example of this when in 2007 one of its defaulted loans was bought for $3.3 million by a vulture fund, which then sued for $55 million — the full amount, plus interest and costs. Debt relief and campaigns like Jubilee are not a panacea, but they have reduced the debt burden of highly indebted countries and limited the ability of vulture funds to profit at the expense of poor countries.

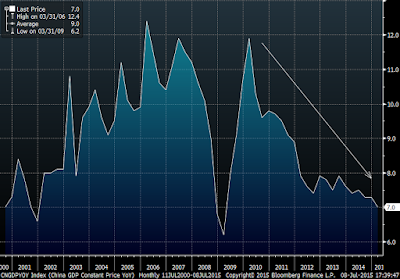

As the quality of U2's songs declined into the new millennium, Africa's growth picked up on the back of the commodity boom. Unfortunately, debt relief and rising commodity prices were not sufficient to ensure sustainable growth, as institutions in Africa remain weak. With commodity prices declining since 2008, growth in Africa has slowed while government spending pressure has not abated. This has led to large deficits, which have to be financed with borrowing. With global yields at record lows, there has been a temptation to borrow in foreign currencies (specifically USD), as the issued interest rate is far lower than domestic borrowing. In recent years, we have seen USD bond issues by a broad range of countries including Ghana, Zambia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Senegal, Ethiopia and Gabon. These

enticing low-interest rates come at the expense of immense currency risk, which has now materialised with the depreciation of African currencies against the US dollar. The following chart shows the performance of the African universe against the USD since 2013.

How costly this depreciation is can be seen in the example of Zambia, where a $750m bond was issued in 2012 when the exchange rate was 5 kwacha to the dollar. Since the time of the bond issue, the exchange rate has weakened by 53% to 7,63 kwacha to the USD. The value of the debt has therefore ballooned from 3,75bn kwacha to 5,7bn kwacha. If the currency depreciates further, this debt burden will continue to rise.

The growth of foreign-currency debt in Africa since 2012 has increased the risk that certain countries find themselves once again in a debt trap. Weak institutions and a culture of patronage in Zambia have led to a mismanagement of the economy, as parties buy votes with populist policies in order to win elections. Michael Sata’s Patriotic Front (PF) made some impossible promises regarding employment, poverty and cost of living in order to get elected in 2011. A ruling party that campaigns with the slogan "More money in your pockets" will always be under pressure to deliver.

Once in power, the PF set about rewarding voters by ramping up spending. The

total budget has grown by 45% between 2013 and 2015, which has caused a large increase in the fiscal deficit. Against a backdrop of falling commodity prices (copper is 85% of exports), the debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 26% to 40.5% between 2012 and 2015. The following chart from Barclays shows t

he past and present: a history of the fiscal deficit dating back to 2008 and the forecast looking to 2016. The fiscal deficit is projected to stay at high levels (8%+) in coming years, and Zambia has reached the point where it is difficult to finance its high level of spending.

These difficulties were emphasised last week when Zambia launched a bond that has the

unwelcome distinction of being

the most expensive dollar debt ever for an African government. They issued at a yield of 9,38%, which is far more expensive than the 2012 bond which was issued at a yield of 5,625%. The desperation of Zambia to borrow is highlighted by the $38,4m “costs” incurred for the bond issue. This is a phenomenal level of expenses for a bond issue, and is an astounding 27 times the $1,4m cost of the 2012 bond issue. The additional “costs” bring the effective cost of debt closer to 9,85%.

Zambia is not alone amongst African countries which have ramped up spending in recent years through the build-up of foreign-currency debt. Ghana finds itself in a similar situation as it tries to launch another USD bond in order to meet it spending requirements, and it is likely to pay a significant price for this. There is a reason that foreign-currency debt is referred to as the

“original sin”, since it has a history of triggering financial crisis.

Both Zambia and Ghana seemed to have reached the point where they are willing to borrow recklessly for political reasons. They need to satisfy the electorate in order to remain in power, and have used borrowed foreign money in a futile attempt to contain currency depreciation. While governments are thinking short term, the debts that they are building u

p in the present will not disappear after the next election, and citizens will suffer the consequences down the line. The extent of financial mismanagement means that both Zambia and Ghana are headed towards a financial collapse. They will soon find themselves in debt trap, beholden to their creditors and institutions like the IMF.

Bono’s services will be required shortly, and they should hope that

U2 is done touring by then.